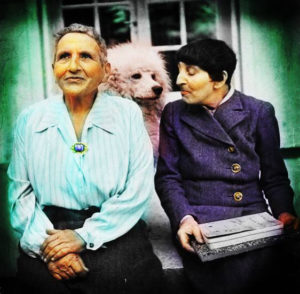

So Famous and So Gay: The Fabulous Potency of Truman Capote and Gertrude Stein is a new book by Jeff Solomon. Read an excerpt below:

From the 1910s until the 1930s, many readers pictured Gertrude Stein lounging on a divan that drew from fin de siècle clichés as well as tropes of silent films. Sometimes she was intoxicated, and sometimes she hallucinated. Sometimes she smoked opium, and sometimes hash. Just as Stein’s followers were portrayed as decadent, so was Stein herself.

Now, although Stein did many things in her long, eventful life, she never lolled on a chaise longue, batting heavy eyelids as she turned from her silver-gilt syringe to lure her victim to his doom. Stein, a practiced hostess, did hold court at parties, and she certainly had a memorable and sexual presence. Yet she seems never to have offered a traditional display of heterosexual accessibility in the service of seduction. She preferred to appreciate the feminine display of others. As for herself, she displayed female masculinity.

Nonetheless, Stein did share one important attribute with the opium queen and the vamp: ethnicity. The orientalist valences of Judaism rhyme well with the Asian accoutrement of the opium den, as well as the public personae of vamps of the silent screen. The marketing of Theda Bara, the first movie star, is instructive here. Bara was born Theodosia Goodman of a Jewish, Polish-born father and a Swiss mother, probably in 1890. She came to prominence in the 1915 film A Fool There Was, inspired by Kipling’s poem “The Vampire.†As the vampire, Bara drags an upstanding married industrialist into decadence, alcoholism, and the grave. The vamp recollects the fin de siècle not only in her textual origin but also in the salons that she hosts and the debauchery that she provokes, and in exotic accoutrements. The film is still remembered today by the oft-parodied “Kiss me, you fool!â€: a corruption of the “Kiss me, my fool!†with which the vamp taunts her prey.[i]

Nonetheless, Stein did share one important attribute with the opium queen and the vamp: ethnicity. The orientalist valences of Judaism rhyme well with the Asian accoutrement of the opium den, as well as the public personae of vamps of the silent screen. The marketing of Theda Bara, the first movie star, is instructive here. Bara was born Theodosia Goodman of a Jewish, Polish-born father and a Swiss mother, probably in 1890. She came to prominence in the 1915 film A Fool There Was, inspired by Kipling’s poem “The Vampire.†As the vampire, Bara drags an upstanding married industrialist into decadence, alcoholism, and the grave. The vamp recollects the fin de siècle not only in her textual origin but also in the salons that she hosts and the debauchery that she provokes, and in exotic accoutrements. The film is still remembered today by the oft-parodied “Kiss me, you fool!â€: a corruption of the “Kiss me, my fool!†with which the vamp taunts her prey.[i]

The success of the film was beholden to the sculpture of Bara’s celebrity persona by Fox public relations. Bara was promoted as the daughter of a French artist and his Egyptian concubine—or was she the Egyptian-born daughter of a French actress and an Italian sculptor? In any event, she was raised in the shadow of the Sphinx. Publicity shots of The Serpent of the Nile surrounded her with skeletons, crystal balls, and other orientalist tat, and Bara was encouraged to discuss the occult in public. When Bara’s Cleopatra was released, in 1917, her name was revealed as an anagram of “Arab Death,†and in interviews she claimed to be the reincarnation of a daughter of the high priest of the pharaohs. Her filmography reveals that any orientalist temptress—Salome, Mata Hari, La Esmeralda—might be projected upon Bara’s “Jewish†features, her large nose and large dark eyes. Bara would make thirty-eight films over the next four years, until Fox dropped her contract and effectively ended her career—but not before intensive publicity had helped her to a prominent seat in the cultural imaginary’s decadent salon.[ii]

Other vamps, including Pola Negri and Alla Nazimova, also had their sexuality heightened through emphasis upon their eastern European or Middle Eastern origin, which was often false. Stein did not need to change her name in order to grease her entry into this harem, for the public drew this conclusion from available evidence. Stein was a Jewish, unmarried, financially independent woman who lived in France and collected art, socialized with the most avant-garde artists, and was herself an experimental writer. Stein’s broad queerness was so pronounced in the American imagination that she was freely associated with behaviors and attributes that were not her own but were nonetheless present in stereotypes of inappropriate female behavior. Putting Stein on the opium couch and in the orientalist harem made her safer and more comprehensible, both more appealing and easier to dismiss.

The reminiscences of Sherwood Anderson and Richard Wright exemplify this mistaken embrace. Anderson and Wright offer evidence that Stein’s broad queerness was so strongly fixed in the public imagination that it could travel freely along nonnormative chains of association. This was the freedom that, when coupled with Stein’s newfound respectability, successfully cloaked the exhibition of lesbian identity and erotics in The Autobiography. Anderson illustrates how this took place in his 1922 essay “The Work of Gertrude Steinâ€:

I had myself heard stories of a long dark room with a languid woman lying on a couch, smoking cigarettes, sipping absinthes perhaps and looking out upon the world with tired, disdainful eyes. Now and then she rolled her head slowly to one side and uttered a few words, taken down by a secretary who approached the couch with trembling eagerness to catch the falling pearls.

The metaphor of falling pearls implies that Stein is so rich that she may strew gems, and so indolent that her only effort is to slowly roll her head. Stein has “tired, disdainful eyes†not from work but from the fatigue that plagues those who exhaust all pleasure. Her sexual appeal is not explicit but is nonetheless inherent in the trope of “a languid woman reclining on a couch.†Kiss me, my Fool![iii]

Anderson wrote within seven years of Theda Bara’s lying languid on a divan in A Fool There Was, smoking with disdain as she rebooted the clichés of the fin de siècle. Note the fantasy of Stein “sipping absinthes perhaps.†And what kind of cigarette is Stein smoking? What makes an opium den besides women smoking on upholstered sofas? Eastern stage dressing, here supplied by Jewish Stein. The image of Stein seductively smoking on her divan offered the added advantage of challenging neither the dominance of heterosexuality nor the idea that female sexual appeal was for the benefit of men.

Yet Anderson’s description also makes plain how Stein’s persona referenced her homosexuality, both generally, through louche bohemia, and specifically, through her partner. We may detect Toklas in the secretary who approaches Stein with “trembling eagerness,†though the actual Toklas was not prone to trembling. Those who did not recognize Toklas did know that single women working in the arts were sexually suspect. Furthermore, the American public believed Paris to be the natural habitat of the lesbian. Until Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness (1928)—which itself positions Paris as a decadent lesbian haven—most available depictions of female same-sexuality were in French literature. This meshed nicely with the sexual freedom that Americans associated with France.[iv]

[i]. A Fool There Was, directed by Frank L. Powell (William Fox Vaudeville Company, 1915).

[ii]. Cleopatra, directed by J. Gordon Edwards (Fox Film Corporation, 1912). For the promotion of Cleopatra, see Eve Golden, Vamp: The Rise and Fall of Theda Bara (New York: Emprise, 1996), 129–34.

[iii]. Anderson, “Work of Gertrude Stein,†6.

[iv]. Radclyffe Hall, The Well of Loneliness (London: Cape, 1928).

Excerpted from So Famous and So Gay: The Fabulous Potency of Truman Capote and Gertrude Stein by Jeff Solomon.

Published by the University of Minnesota Press. Copyright 2017 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota. Used by permission.

Read More on Epochalips.com about Gertrude Stein By Jewelle Gomez